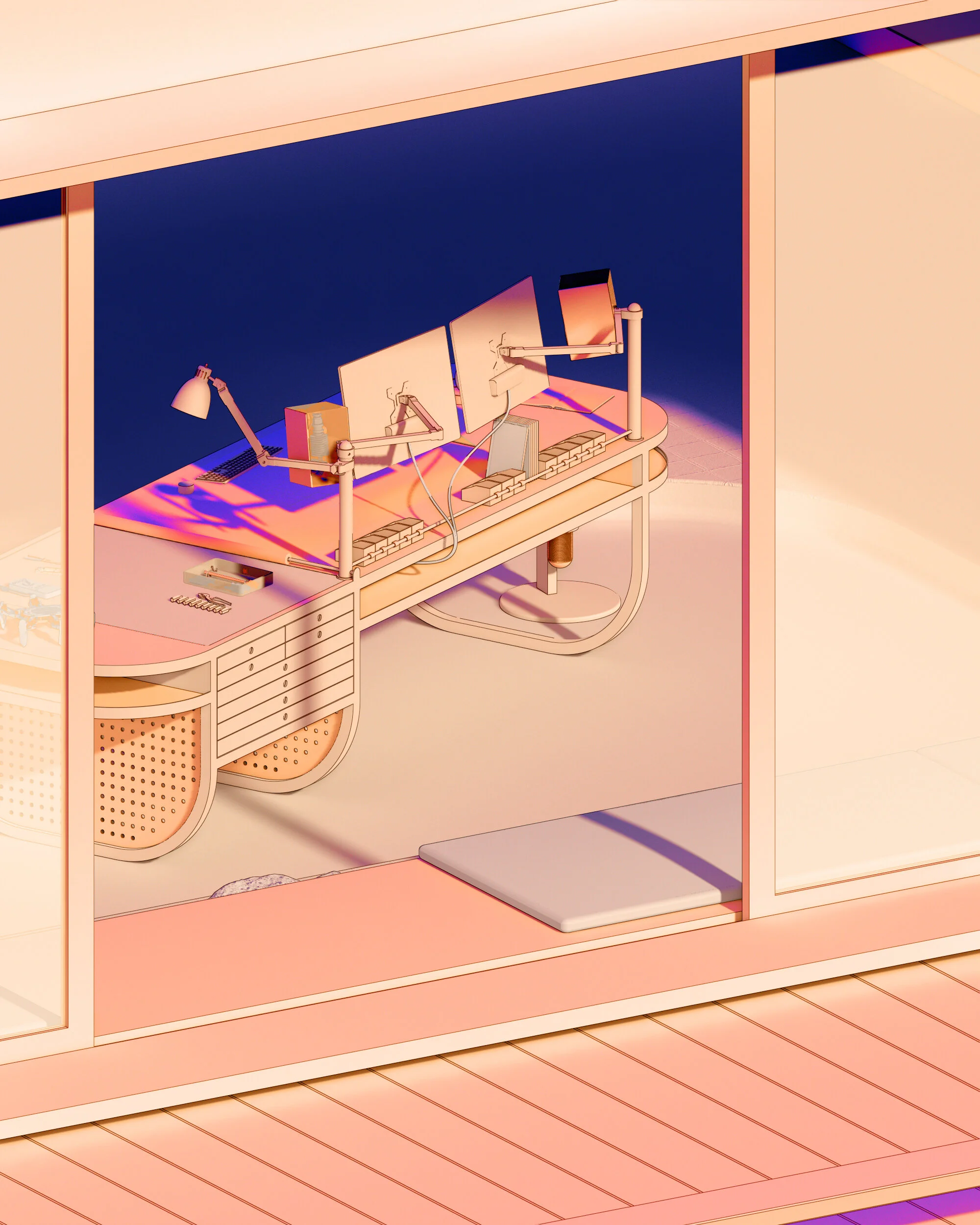

CLOUD GARDEN STUDIO

AN OPEN AIR STUDIO & WORKSPACE FOR THE MODERN DAY RENAISSANCE PERSON

The Cloud Garden Studio explores the nature of ‘simple complexity’ in our working environments and how, simply through a direct connection to nature, our place of work transforms into a contemplative retreat.

Below are additional moments within the scene, along with a brief walkthrough of the 3D modeling and rendering process.

Scene, lighting, and material design by Alexander